By Mahlia Lone

The tempestuous 15 year relationship of Z.A. Bhutto and Husna set against the backdrop of his meteoric rise and fall. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto met Husna Sheikh at Billo and Khalil Omer’s house in Dhaka in 1961, he was, at only 34 years of age, Ayub Khan’s young and fiercely ambitious foreign minister, a Sindhi feudal and an Oxford educated barrister, while she was married to a bourgeouis nationalistic Bengali lawyer Abdul Ahad and mother to two toddler girls.

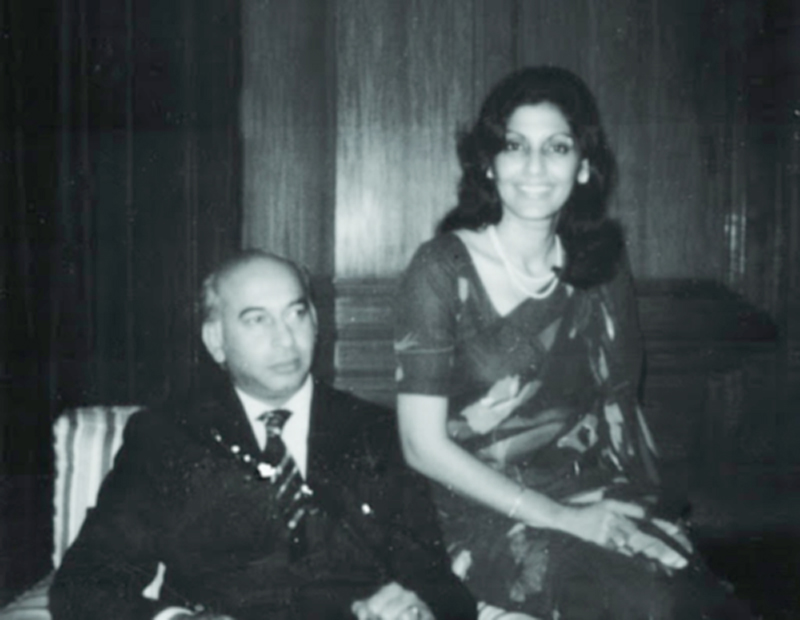

Not the girl next door, Husna was a rivetingly attractive, sari clad, husky voiced, tall, svelte, dusky beauty, with a mixed Pathan-Benagli ancestry. Husna challenged Bhutto that evening, she recalls, on West Pakistan’s imperialism towards the East and how it would lead to the Bangladeshi movement, thus capturing his attention with her “aggressive confidence” and oozing sex appeal.

But Bhutto was a nefarious philanderer. Not happy in her marriage, she reportedly played hard to get with Bhutto at the outset because, knowing his reputation, she didn’t just want to be his latest conquest. Bhutto already had one cousin-wife at his estate in Larkana and a second, the glamorous and elegant Kurdish-Iranian, Nusrat ensconced in his Karachi home at this point.

Bhutto and Husna were not only physically compatible, but had formidable intellects to match and the affair progressed to a stage that in 1965, Husna, leaving her husband behind in Dhaka, confidently moved to Karachi with her daughters, virtually penniless. “The chemistry was undeniable,” said Husna to Jugnu Mohsin in her 1990 interview for The Friday Times. “Both Zulfi and I were charged with something beyond each other. It was a vital, exuberant feeling.”

In her autobiographical novel, My Feudal Lord, Tehmina Durrani writes that Mustafa Khar facilitated the still hush-hush affair, picking and dropping Bhutto in Karachi to Husna’s residence. On one occasion he even he witnessed a defiant Husna slamming the door shut in Bhutto’s face. It became a stormy, tumultuous affair between two head strong and independent minded people. Though he was a powerful and charismatic leader revered by millions, it must have been a novel experience to have a woman dependent on his good will stand up to him, unlike his sycophantic followers.

Managing an introduction to Sheikha Fatima of Abu Dhabi, Husna got a contract to decorate her Abu Dhabi palace in 1967. It was with these proceeds, Husna said, that she became the owner of two Karachi properties, a Moorish style villa called Manzil, in close proximity to Bhutto’s Clifton abode Al Zulfiqar, as well as a cottage at Hawk’s Bay, and later a flat in London, amongst other investments.

Finally in 1969, Ahad divorced his errant wife. Bhutto was on the verge of marrying her when he got arrested, writes Mohsin. Disenchanted, she stayed out of his way for many months. The first day she returned to her home in Karachi, he silently came and stood behind her. Thinking it was her sister, she asked her what she wanted, turning around to see him weeping uncontrollably.

“How can you do this to me?” he asked her. “You are my destiny.” “He cried like a child and made me promise I would never leave him,” said Husna, “I realized that day how much I loved him.” Stanley Wolpert in his 1993 biography Zulfi Bhutto of Pakistan: His Life and Times writes that though Husna was a ravishing beauty, it was not simply her physical charms that hypnotised Bhutto.

She told Wolpert that she was the first woman the philandering politician had ever loved who could think, talk and understand power politics as he did. Even as she sated Bhutto, she stimulated his mind, body and spirit, “rousing him to peaks of excitement he had never known”. Pandering to his massive ego, Husna and ZAB discussed politics and world affairs after “the flames of passion had died down….

For Zulfi’s proud, vain, arrogant, insecure, clever, scheming, easily bored, spoiled psyche nothing was as comforting as a beautiful woman who devoted herself fully to his needs, desires, and dreams, rousing his hopes and calming his darkest fears,” Wolpert writes. According to Husna, soon after Bhutto became Prime Minister in 1971, he married her in December of that year.

The clandestine nikah was performed by Maulana Kausar Niazi and was witnessed by Mustafa Khar. As a marriage gift she received a Koran inscribed simply in Bhutto’s own hand with the words, “To my wife Husna.” Neither the Koran, nor the nikah naama were ever found though years later the martial law government conducted many raids to recover them.

Rumour has it that upon hearing the news of the marriage, Begum Nusrat Bhutto tried to commit suicide with an overdose of pills in Islamabad and was hospitalised at the Civil Military Hospital Rawalpindi. Husna had wanted Bhutto to claim her publicly, but he ended up promising Nusrat that she would remain the official First Lady, and he would refrain from giving Husna his name.

However, Husna was compensated handsomely by becoming the power behind the throne. From the time Bhutto became Prime Minister in December 1971 until the coup in 1977 when Husna sought refuge in London, she ran a shadow kitchen cabinet at her Karachi residence Manzil. Bhutto would meet her at least 4 to 5 times a month and never stayed away from her for more than ten days at a time.

She even accompanied him on official trips abroad, though in an unofficial capacity. What better way was there to seek out the Prime Minister than when he was in a relaxed and jovial mood while being entertained by his favourite? Ministers and senior party officials desirous of currying the PM’s favour eagerly sought an invitation to Manzil and Husna’s ear. Many political appointments were decided in this way.

“Husna Sheikh was the Madame de Pompadour (official mistress of Louis XV, who helped him run France) of Pakistan,” said PPP politician Salman Taseer. Husna recalls of Bhutto, the political leader and PM, “He believed in his own mission, but he believed his hands were tied. Kemal Ataturk was his great hero. I would ask him why he was in such a hurry. To which Zulfi would reply that he was in a hurry because he knew they were going to kill him.”

She also said that the elections of 1977 were not rigged by him, but by his Chief Ministers. “Will someone tell my CMs not to ruin 20 years of my hard work?” he asked her. The situation soon snowballed out of his control. When the General Zia led military coup occurred, Husna said she was already in London where her eldest daughter was delivering a baby. She did not return.

Though she was deeply resented by Benazir, who had obviously sided with her mother, Husna said Murtaza kept her in touch with Bhutto’s ordeal over the next two years, while ZAB was confined in a cramped prison cell, rapidly losing his health. First, Husna hired British lawyer John Mathews to defend Bhutto in his murder trial held before the Lahore High Court, but the Pakistan government disallowed it on grounds that a foreign lawyer could not appear in a court until he had practised in Pakistan for a year.

Then, she claimed to have pleaded with Sheikha Fatima to have the Emir Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan ask Zia for clemency in the sentencing, but Zia turned a deaf ear. When Nusrat and Benazir visited Bhutto in jail in April 1979, Murtaza told Husna, it would be the family’s last meeting with him. He was hanged the next day.

After Bhutto’s hanging, a deep depression took a hold of Husna and she contemplated suicide she said. However, she managed to pull herself out and has gone on to live out the rest of her life in relative peace and prosperity. Her union with Bhutto produced her youngest daughter Shahmeen and it was the thoughts of her family that gave her the strength to continue.

Husna is now a beautifully preserved octogenarian. She never remarried.