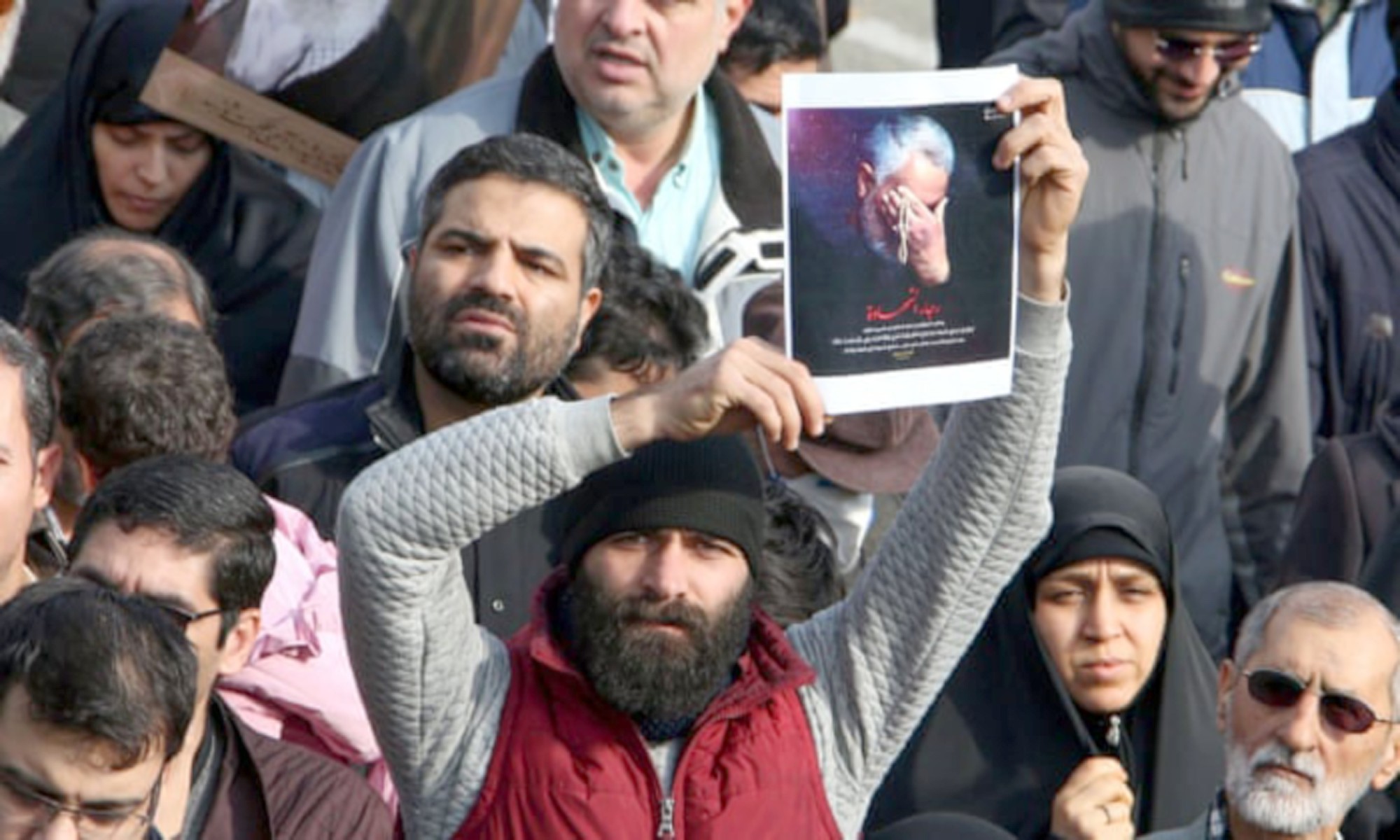

The Quds force leader had the status of national hero even among secular Iranians. His death could act as a rallying cry

By Mohammad Ali Shabani

The US has assassinated Qassem Suleimani, the famed leader of Iran’s Quds force, alongside a senior commander of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. To grasp what may come next, it is vital to understand not only who these men were but also the system that produced them. Nicknamed the “shadow commander” in the popular press, Suleimani spent his formative years on the battlefields of the Iran-Iraq war during the 1980s, when Saddam Hussein who at the time enjoyed the support of western and Arab powers was attempting to destroy the emerging Islamic Republic.

But few people remember that his first major mission as commander of the Quds force the extraterritorial branch of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards involved implicit coordination with the United States as the US invaded Afghanistan in 2001. The Taliban were, and to some extent remain, a mutual enemy. That alliance of convenience ended in 2002 when the US president George W Bush notoriously branded Iran a member of the “axis of evil”.

In the years after, Suleimani laboured to bleed the US military in places like Iraq. He succeeded. After having spent trillions of dollars and lost thousands of troops, Washington withdrew from Iraq in 2011 partly as a result of Iranian pressure on the Iraqi government. Suleimani had little time to celebrate, however. His attention was turned to containing fallout from the Arab spring, propping up the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad.

That development saw the creation of a region-wide network of Iranian-backed militias numbering more than 100,000 men, unprecedented Iranian military collaboration with Russia, and the transformation of Hezbollah into a force capable of operating on significant scale outside Lebanon’s borders.

By 2014, when he successfully halted Islamic State’s attempt to overrun Iraq, Suleimani was being feted as a hero among Iraqis alongside the local commanders, including al-Muhandis. The same response was evident in Iran, where he quickly became a household name and was rumoured to be a potential future president a trend that was strengthened by the Trump administration’s unilateral withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018.

So the US has not merely killed an Iranian military commander but also a highly popular figure, viewed as a guardian of Iran even among secular-minded Iranians. And with the assassination of al-Muhandis, the Trump administration has put itself in the position of having killed the operational commander of a large branch of the Iraqi armed forces.

Some will characterise the deaths as a huge blow to Iran’s proxy capabilities and wider policy in the region. But such an approach ignores how the Iranian system is structured. Suleimani’s successor as Quds force leader his long-time deputy, Esmail Qaani was announced within 12 hours of his death. Suleimani was charismatic and played a personal role in cultivating many of Iran’s relationships in the region, those ties do not rely on him alone.

Rather, they are the product of extensive and deep bonds that often go back decades and in many instances involve family ties. Suleimani was well aware of the dangers of the job, as was his singular boss, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who in years past deemed him a “living martyr”. So succession planning was never far from his mind. Indeed, 62-year-old Suleimani gave his younger lieutenants considerable operational authority.

In practice, this has meant the elevation of a new generation of Quds force operatives, some of whom Suleimani had already begun positioning in vital posts: a case in point is Iraj Masjedi, the current Iranian ambassador to Iraq. So what comes next? Predictably, the Iranian authorities have promised “severe retaliation”. How that unfolds in practice is anyone’s guess. There is certainly no shortage of US targets in the region.

But Suleimani may, with his death, have already achieved the greatest revenge of all, and without firing a single bullet: namely, his ultimate objective of ending the US military presence in Iraq. If he was indeed behind the attack on the US military base that ultimately precipitated his own assassination, then he has probably succeeded in trapping the US into initiating its own ejection from Iraq.

So far, most Iraqi decision-makers, from the caretaker prime minister to the country’s highest spiritual authority, have condemned in no uncertain terms the violation of sovereignty that the assassination entailed. As for Trump, he is stuck with the same problem he faced before Friday’s strike. The United States is no closer to the much-touted “new deal” with Iran, which the president boasted would eclipse that negotiated by his predecessor. Whatever remaining diplomatic off-ramps there were are rapidly crumbling. Meanwhile, at a time when his unprecedented sanctions had stirred unrest inside Iran, the political elite has just been handed a rallying cry.

The strike on Suleimani, whose status approached that of national icon, will harden popular sentiment against the US while simultaneously shoring up the regime. For all his crowing about the decisive blow dealt to an insolent enemy, Trump may be about to discover that the problem with martyrs is that they live forever.

M. Ali Shabani is a researcher at Soas University of London, where he focuses on Iranian foreign policy.