Frustrated by the lack of an Afghanistan war strategy from the White House, Sen. John McCain on Thursday unveiled his own plan for winning America’s longest conflict.

“We must face facts: We are losing in Afghanistan, and time is of the essence if we intend to turn the tide,” the Arizona Republican, who chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee, said in a statement. The proposal is more of a mission statement for how to win the nearly 16-year-old war than a blueprint. It calls for: increasing “U.S. Counter terrorism forces” but does not include a precise number of new troops; imposing unspecified “diplomatic, military and economic costs” on Pakistan for its continued support of groups fighting Afghan and U.S.-led forces; and tying U.S. aid to Afghanistan on to-be-determined “benchmarks” on issues like rule of law and the fight against rampant corruption.

While the proposal does not specify how many more troops should serve in Afghanistan, it says the administration should set force levels “based on political and security conditions on the ground” and “unconstrained by arbitrary timelines.” McCain packaged his ideas in a nonbinding “sense of Congress” resolution that he aims to attach to an annual military spending authorization bill, on track for debate next month. Senior Trump advisers have waged an internal war over the way forward in Afghanistan, with the president himself deeply skeptical of deepening America’s involvement in anything that might resemble the nation-building projects he denounced on the 2016 campaign trail. Some top aides say they face a “victory problem” how to define success. There is a broad consensus that America’s foremost national security goal is to prevent Afghanistan from slipping back into its pre-9/11 state as a safe haven for extremists plotting to strike at America or its allies.

But beyond that, there have been three distinct camps, according to several top Trump aides. Senior adviser Steve Bannon has fueled Trump’s instinct to be skeptical of proposals to send more troops. National Security Adviser Gen. H.R. McMaster has pushed for a broad military, economic and diplomatic commitment to Afghanistan (Bannon has joked with other West Wing aides that Trump should send McMaster to run the war). Defense Secretary James Mattis has argued for a narrower mission in which U.S. forces train and equip their Afghan counterparts and provide some limited battlefield role, while leaving decisions about institution-building to the government in Kabul.

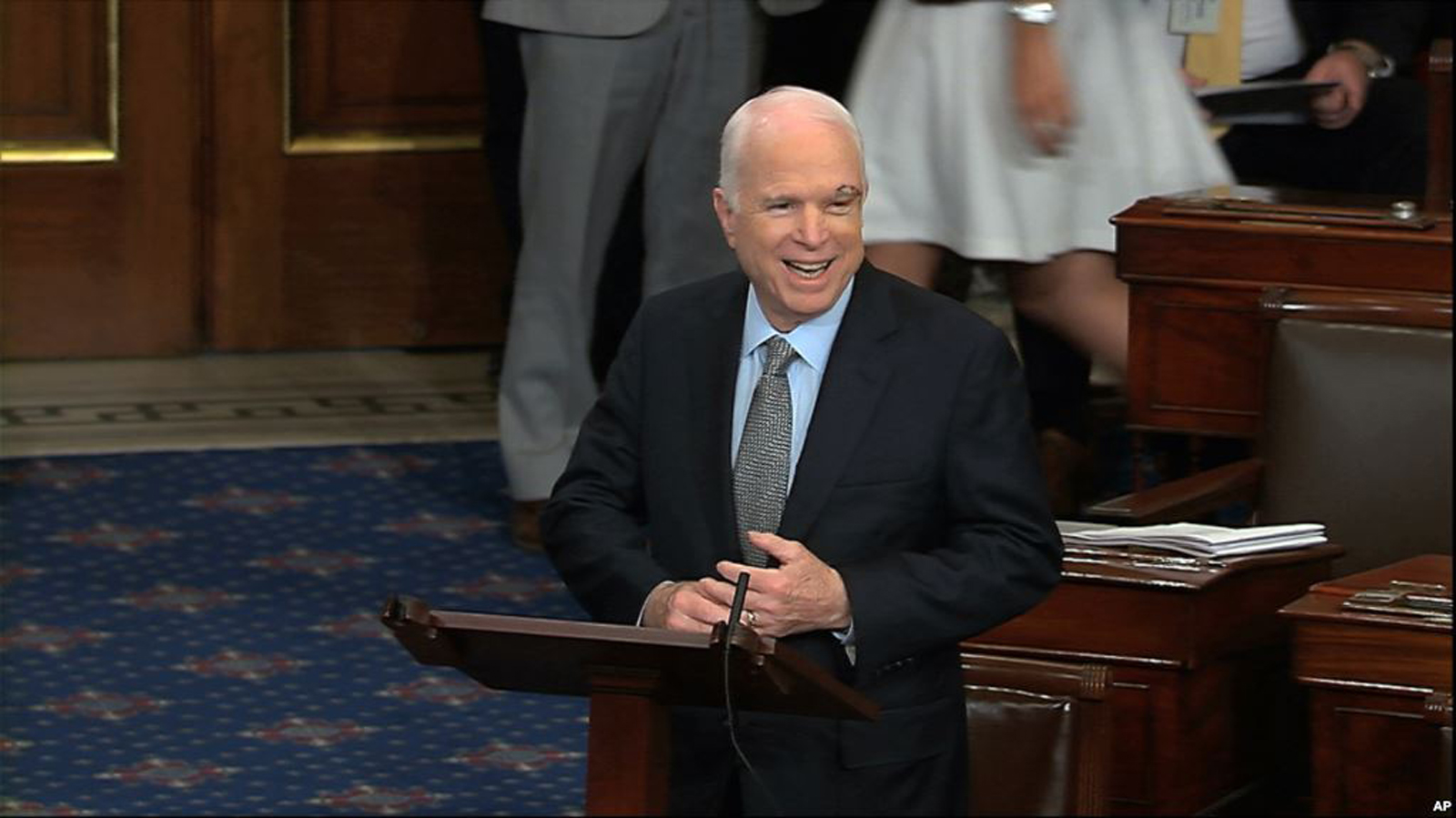

Mattis has been open about the fact that U.S. strategy will likely require a residual force to carry out counter terrorism operations, a prospect one senior aide said particularly frustrates Trump. The infighting, as well as vacancies in key policymaking posts across the departments of State and Defense, has crippled the effort to draft a new strategy. “Nearly seven months into President Trump’s administration, we’ve had no strategy at all as conditions on the ground have steadily worsened,” McCain said. “The thousands of Americans putting their lives on the line in Afghanistan deserve better from their commander in chief.”

The senator had warned Mattis at a mid-June Senate Armed Services Committee hearing that his patience was wearing thin.

“Unless we get a strategy from you, you’re going to get a strategy from us,” he scolded from the dais. At the same hearing, the defense secretary acknowledged that “we’re not winning” in Afghanistan and predicted he would be able to lay out the administration’s proposal a month later. But at a mid-July question-and-answer session with reporters, Mattis admitted that he still did not have a plan, even as he tried to deflect questions about internal divisions and delays.

“Welcome to strategy,” he said. “Seriously, this is hard, and there’s a reason we’ve gotten into some wars in our nation’s history and didn’t know how to end them.” Mattis also alluded to the vacancies at the Pentagon, describing “the number of empty parking places.” The Pentagon made clear early this year that it wanted “thousands” of additional troops, on top of the roughly 8,400 U.S. forces and about another 7,000 from NATO allies. But in mid-July, Mattis declined to say how many.

“I know everyone’s batted around numbers, and they may turn out to be right. But I’m not giving it any credence right now,” he said.

Since George W. Bush unleashed U.S. military might against the Taliban on Oct. 7, 2001, some 2,400 Americans have died in the conflict and more than 20,000 have been wounded. Barack Obama surged tens of thousands of troops into Afghanistan in 2009 but later drew frequent criticisms from Republicans, who accused him of focusing on withdrawing U.S. forces rather than defeating the Taliban.

Obama aides said their main goal was making local security forces self-sustaining in order to extricate the United States from a seemingly intractable conflict. The war bedeviled both of Trump’s predecessors. It falls to the former real estate developer with a penchant for short declarations on even the most complex issues. Years before he captured the White House, Trump was calling for a withdrawal.

“We have wasted an enormous amount of blood and treasure in Afghanistan. Their government has zero appreciation. Let’s get out!” he tweeted in November 2013. “We should leave Afghanistan immediately. No more wasted lives. If we have to go back in, we go in hard & quick. Rebuild the US first,” he tweeted in March 2013.